Just as her personal and social life was marked by tensions between her marginal status as a nun and the central role she played in the cultural and intellectual life of New Spain under the patronage of two successive Vicereines, her writings are often marked by tensions and contrasts between competing aspirations.

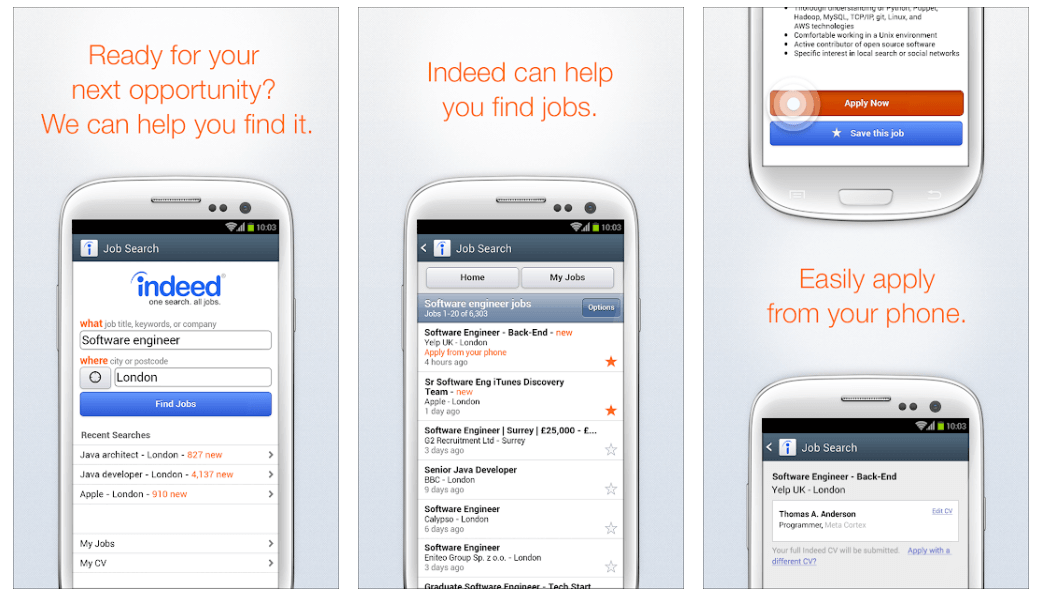

INDEED.COM VOX NUTRITION SERIES

For most of her life, she maintained close friendships with many members of the political and cultural elite of New Spain, and she achieved a series of literary and intellectual feats that led one of her admirers to describe her as “Madre que haces chiquitos a los más grandes ” (“a Mother who makes the greatest so small”). Although it may have been possible for Sor Juana’s choices and life circumstances to destine her for a life of opprobrium and relative obscurity, given her birth out of wedlock, her oppressive and hierarchical colonial context, and her membership in a religious order, she ultimately became one of the most famous polymaths of the 17th century.

Both her life and her writings are marked by a series of tensions and contrasts.

“But who has prohibited women private and individual studies? Do they not have a rational soul like men? … What divine revelation, what determination of the Church, what dictate of reason made for us such a severe law?” -Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, in Autodefensa Espiritual (translated from Tapia Mendez 1993).īorn at the end of the Spanish “Golden Century,” Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz is, in many senses, the perfect embodiment of the Baroque spirit. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Portrait of Sor Juana attributed to Nicolás Enriquez de Vargas (18th century)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)